Restoring a Forgotten Volume of Edward S. Curtis’s The North American Indian

Published

Agnieszka Czeblakow, Curator of Rare Books and Head of Research Services

On a high shelf in the rare book vault, a brown, unassuming cardboard box has sat quietly since 1995. In 2023, while preparing the rare book collection for a two-year project of reclassification, shifting, and providing better housing and storage to its vast collection of oversized materials, I came across this box, naturally wondering, as curators often do, what is inside. Inside, I found a dilapidated portfolio and a brief catalog record note printed on a dot matrix printer for Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian (1907-1930), a monumental and complex photographic project that sought to document what Curtis believed were “vanishing” Indigenous cultures across the United States.

The note included standard bibliographic information used to catalog books: title, author, and publication date, as well as a brief description of the actual portfolio, noting that it “has various plates, most oversize, some tissue, most damaged.” Intrigued by the description, I opened the portfolio, revealing 14 photogravures, many printed on thin tissue paper, all messily scattered inside the portfolio, many battered by time, cut or torn by previous owners, and discolored from a variety of chemical and natural processes [ed. note: Photogravure is a process for printing photographs by exposing a light-sensitive gelatin tissue to a film positive. The tissue is then applied to a copper plate, which is etched. The technique produces rich and detailed continuous tones and so was often used for art photographs].

Not wanting to disturb the contents further, I reached out to the Head of Conservation at Tulane Libraries, Carrie Smith, asking for input on the best way to stabilize the prints and make the book useful again for teaching and learning. A few days later, Carrie sent me a condition report and treatment proposal for approval.

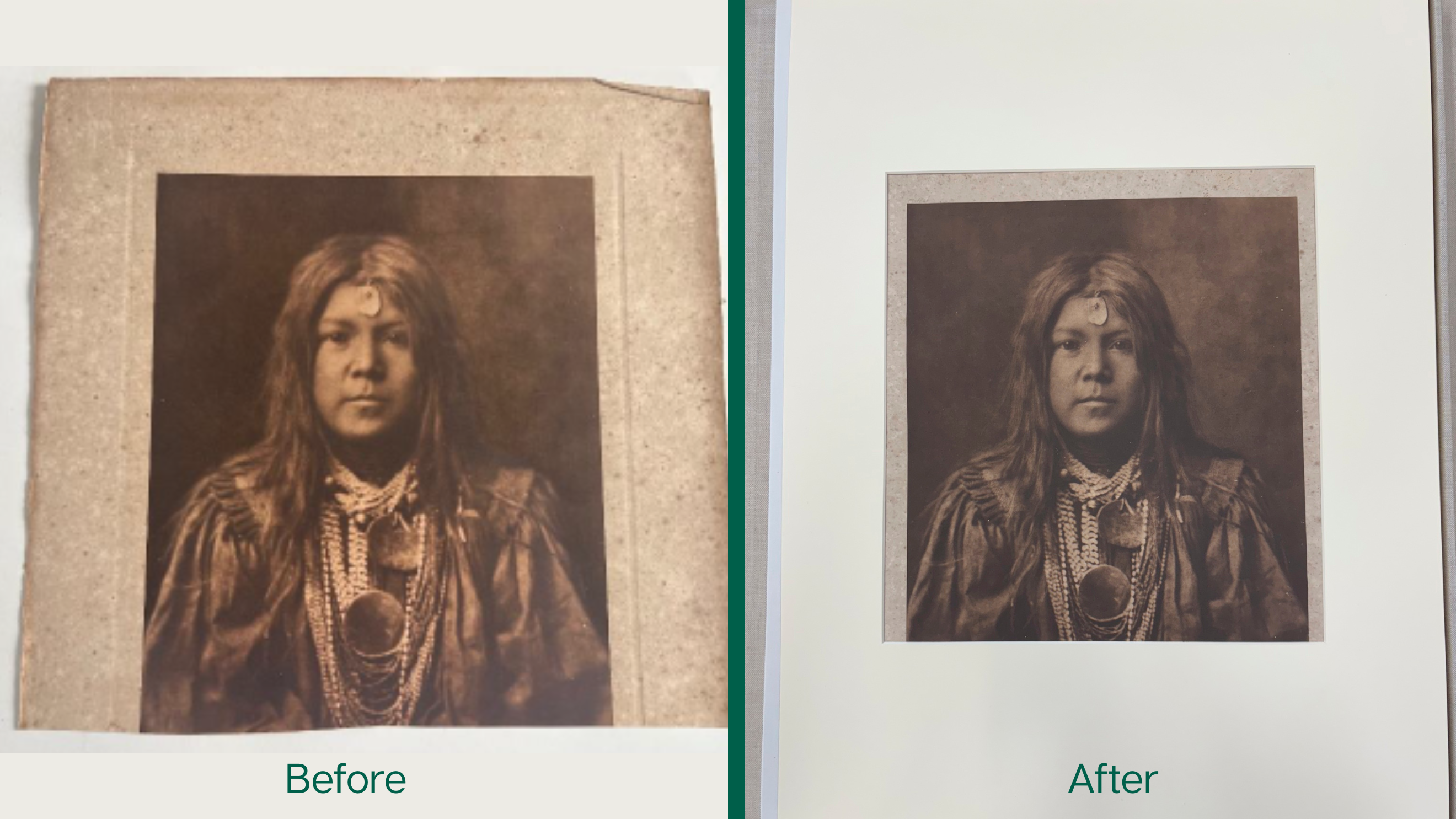

The treatment for these photographs was fairly straightforward, but the difference is dramatic. Because it was a big job, all materials were sent to Fleur du Livre, a private conservator in the city.

Because many were printed on tissue paper, they are challenging to handle. To make matters worse, they were attached to backing boards and window mats made from acidic materials that had discolored and deteriorated over time. The matted photogravures were stored in the original portfolio (also deteriorating), and everything was in an acidic cardboard box.

Erin Albritton at Fleur du Livre used a poultice to soften the adhesive and remove the photogravures from their backing boards, then gently humidified and flattened any that had become wrinkled. She made new window mats from conservation-grade mat board, and carefully hinged the photogravures into these new mats. The mats allow for safe storage and handling of fragile photogravures.

All of the mats went into new, custom-made boxes. The fourteen prints were split into two boxes, so that one box wouldn’t be too heavy. The original portfolio was retained and given a new box, making three new boxes in total. The original box and mats were also retained, so we can really see the difference.

After about four months of treatment, Curtis’ single volume is back on the shelves in the TUSC’s Rare Book Collection. Its conservation serves as a powerful reminder of the fragile nature of archival materials and books, the complex legacies they carry, and the urgent need for ongoing conservation. The work of conservators—often invisible but always essential—not only prolongs the life of damaged materials but also enables critical reflection and dialogue on ethical stewardship of the historical record.

The restored volume will be on view in the HTML lobby on November 4. Please check library.tulane.edu for details of the event closer to the date.